The Strong-Willed Mom: A Tribute to Teachers

Many DIBS supporters might not know how much this program was originally inspired by teachers. Really just one teacher, actually. This post is a small tribute to that very teacher who retires later this month after a twenty-year career as a kindergarten teacher in one of Omaha’s highest-poverty schools. That teacher is probably best known as “Ms. Orrick” to the some 400 kids who have passed through her classroom since 1998 – but she is known as “mom” to our founder. And to know her story as a single mother and as an educator is to know how this whole darn thing came about…

Sometimes I think my selective memory is one my greatest assets as a social entrepreneur, though it’s a little scary when it carries over to my personal life. For example, I can’t recall the time that I told my mom she was “being lazy” when I was in middle school and she told me I needed to start doing my own laundry – yes I was a real stand-up teenager – but I do remember that I also helped her study for her math exam that she had to take as part of her teaching masters program at the University of Nebraska-Omaha.

What makes this “lazy” comment even more cringe-worthy, though, now that I have 20+ more years of life experiences behind me, is that my mom’s move to handoff laundry to me and my brother was the result of my father leaving the family and her need to go back to work after being a stay-at-home mom much of our upbringing. And that Masters Program. Yeah, same thing. She knew she could advance her skills and have a little higher income if she did night and weekend classes while working as a public school teacher.

Some “lazy” mom I have, right?

My mom often reminds me of one other comment I made about that same age. No doubt while trying to get under her skin I, apparently, (see… very selective memory…) told her that I wasn’t sure why she was complaining so much about her teaching job, and explained that I didn’t know how it could be so hard since she only works until 3:30pm and has summers off. (Am I the only one who wishes vocal cords didn’t develop until your 20s?!).

How or why she didn’t just put me on the streets I may only learn as my 11-month-old daughter grows up, assuming she has the same “strong-willed” edge as her father. But she didn’t put me out. And, in 2001, I can only assume that it felt like much of her work was done: I went off to college and got a bachelor’s degree in architecture. In 2005 I took a fairly high paying corporate sector consulting job, and helped launch a new division within the organization I worked for.

But by 2008, it was clear that this story wasn’t quite complete. Inspired by my mom and the stories she used to share about the hardships that the students in her high-poverty elementary school were facing, I decided to apply to Teach For America and was accepted to teach in New Orleans.

I wish I could tell you that this move was 100% out of respect for my mom’s work. It was, partially, but if I’m being honest I also applied to Teach For America pretty convinced that I was going to become the type of teacher you see in the movies – inspiring children growing up in poverty to excel beyond their wildest dreams.

Like so many Americans, I had heard all the stories about how our school system was broken, and how there was a need for “talented” young women and men to enter the ranks.

My “talent” and work ethic had led me to finish architecture school in four years and had led me to be a top-performer in my company – I was ready to be a teacher and prove that if teachers just work hard and roll up their sleeves, anything is possible.

In many ways, I was ready to prove that my mom just need to work harder. That she wasn’t doing enough for her students.

Worse yet? My mom actually knew that this was my underlying sentiment – we would debate often about the role of teachers and about failing schools. Yet, when I called to tell her I was accepted to Teach For America but that I got placed in New Orleans and not my desired New York, she had a word-for-word response that I will never forget:

“David, they must really think you’re special to put you in New Orleans.”

Yes – and for those who don’t know Liz Orrick – just know this blog post could also be titled “A Tribute to the Most Unconditionally Supportive Mother in the World.”

At this point you need to know that my mom is a kindergarten teacher, and that teaching kindergarten felt like child’s play to me when I joined Teach For America. Instead I applied to do the “real work” and teach high school – ultimately with visions of becoming the next Robin Williams in the New Orleans version of Dead Poets Society that was going to play out in my classroom.

In a series of strange plot twists, though, I got placed in first grade.

I got placed in one of New Orleans’ lowest-performing charter schools.

And I got placed in a classroom with 29 students.

Usually at this point when I share this story with teachers there is laughter. Almost excitement. They allllllllll know how this story is going to end.

Somehow I didn’t.

And what I’m afraid of is that too many Americans today – especially business leaders – also don’t know how this story is going to end.

On my first day of school I took a picture, similar to the ones below, but that I can no longer find. My mom used to take pictures of me on the front porch of our house on the first day of school every year. On my first day teaching, she made me promise I’d also send her a picture on my front porch. I did. Then I drove to school.

Sorry, photo gallery is empty.

I won’t try to explain how miserable my first day of school was, or how the 2008-2009 school year was the longest year of my now 34-year life – by miles. Again, teachers know where this story goes.

But I will say that upon finishing up my first day teaching, exhausted and in an utter state of uncertainty about what I had gotten into, I did the only thing I could think to do – I called my mom and told her that I had made a mistake. She would have been 100% justified to smile at my circumstance or even say “David, I told you this was going to be rough.” Instead, I will never forget her words:

“David, the first day is always tough. You are going to have such an impact on your kids, just stick with it and call me whenever you want to talk.”

Like her son, my mom also lies sometimes. As teachers also know, the first day of school isn’t actually “always tough.” Kids are actually often on their best behavior, feeling you out as a disciplinarian and educator.

The first day isn’t “always tough.” The profession is “always tough.”

I was a miserable teacher my first year. Miserable. I got fired from my school for being so terrible with classroom management, and professionally humiliated by administrators throughout the year who just thought “he doesn’t have it.”

In my lowest moment, the leader of our parent charter school operator told me as early as September, in front of a whole staff meeting, that I was likely not going to make it to Thanksgiving. I waited for the meeting to end, then tried to hide for a moment in the hall while the tears rolled down my face.

A teacher covered me for ten minutes so it wouldn’t traumatize the students. Then I ran a morning meeting for a few minutes before a student asked “Mr. Orrick are you okay?” which unlocked the next set of tears and, in another plot twist, my students tried to comfort me one-by-one (some Robin Williams I am…).

This story does get better my second year, as educators can also relate (so… if there are first year teachers reading and debating their plans for August…please stick to it!!! It is very unlikely you are worse than me and, even if you are, it doesn’t mean you “can’t” – you just “aren’t…yet”).

After my first year I was recruited by a principal and assistant principal who observed my classroom, watched a student dropkick another student in the chest during centers time, then offered me a job helping launch their turnaround school in New Orleans’ Upper 9th Ward. When I later asked why he hired me the principal said something I’ll also never forget:

“Sometimes the teachers who get burnt the hardest are the ones who refuse to let the same thing happen to them their 2nd year teaching. We think you’re that person.”

They were right. I was by no means “exceptional” my 2nd year, but with the Teach Like a Champion training my school wrapped around me – and the refusal to make the same management mistakes twice – I was pretty darn solid.

Using the Rearview Mirror to Look Ahead

My mom’s career is behind her now, and you can’t turn back the hands of time. But you can learn, and you can try to prevent others from making your same mistake, which is why I’m writing this now and holding back tears.

For the last eight years since leaving the classroom I have been working on a puzzle. The puzzle has revolved around a couple guiding questions:

- Why do we let educators systematically fail – especially in their early years?

- And how can we prevent this for future educators, especially those like my mom who serve high-poverty students and families?

I’ve learned how complex this challenge is (and been humbled again many times over…).

But I have also come to a pretty clear conclusion that there is one, single, highest-leverage thing that we can do as a society to help put elementary teachers on a better footing as professionals: Provide them with the supports that are required to ensure that every child has a great book to read at home, every night, and a desire to read that book for fun.

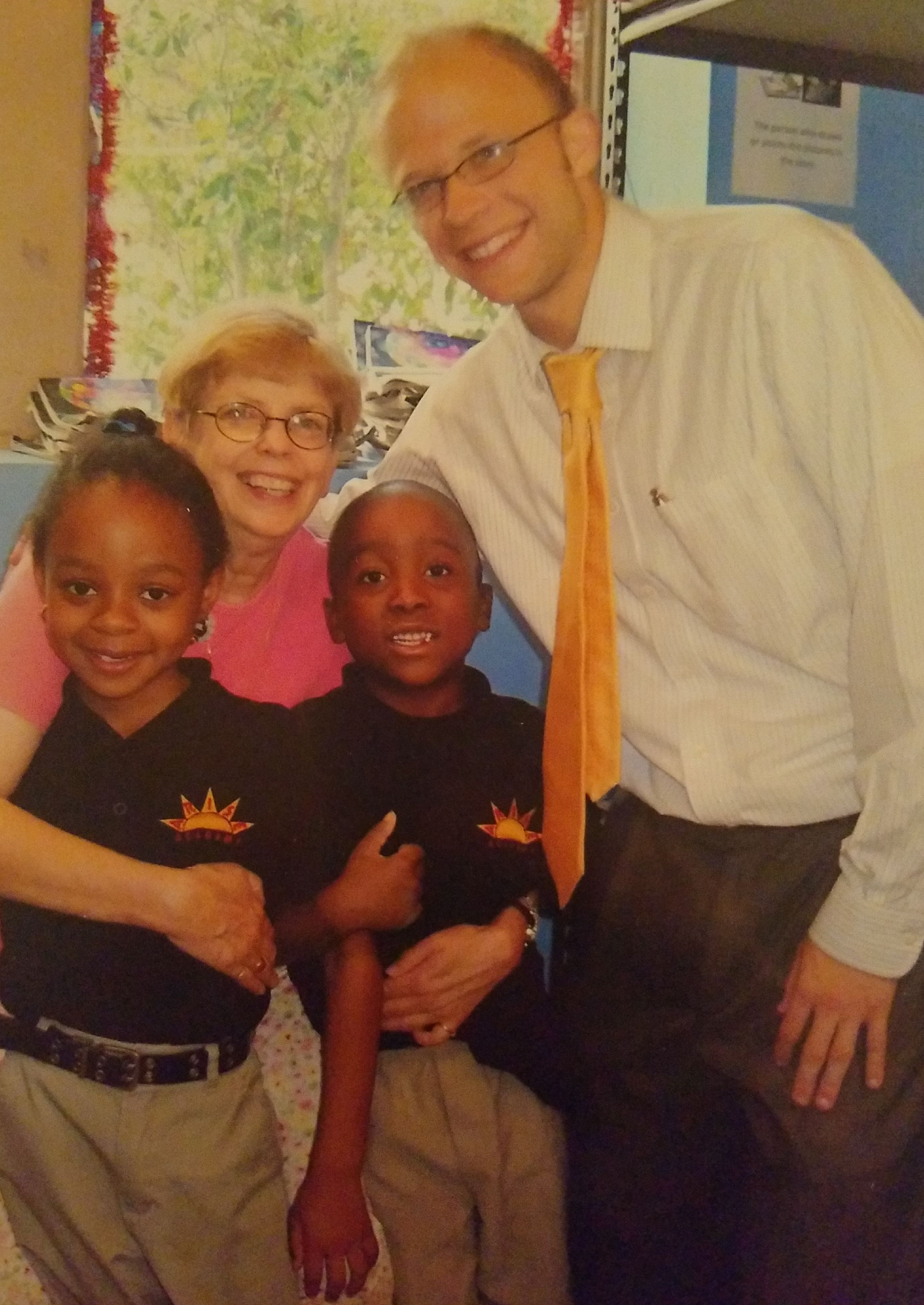

Out of this conclusion DIBS for Kids was born and… spoiler alert…Liz Orrick was sitting in the front row when we presented the program to her school and was smiling ear-to-ear ready to give what was a WAY less-than-perfect program at the time a chance in her classroom (no doubt she actually ran a behind-the-scenes marketing campaign after the meeting trying to get other teachers to join too, if I know my mother…).

At DIBS we love nothing more than meeting with teachers and just hearing your stories and learning if there are ways we can support you. But we will settle for taking meetings with any business leaders who you think need to hear this story and to hear why we as non-educators are often so darn backwards with how we think about education and the role of teachers.

And now just 10 years after Teach For America… and at least in a small way…I hope to carry my mom’s legacy as an educator alive and well here in Omaha as long as this program persists.

David is the founder of the Omaha-based literacy nonprofit DIBS for Kids. DIBS is designed out of his frustrations as a public school teacher, and his desire to provide other teachers with the support he wished he had. He is a proud husband and father, and a Nebraska native (Yes…he is a Husker fan if that wasn’t assumed).

Previous Post

Previous Post